India’s Solar Revolution: Was Adani’s Billion-Dollar Bet Built on Bribes?

Adani's Renewable Energy Victory and Its Fallout

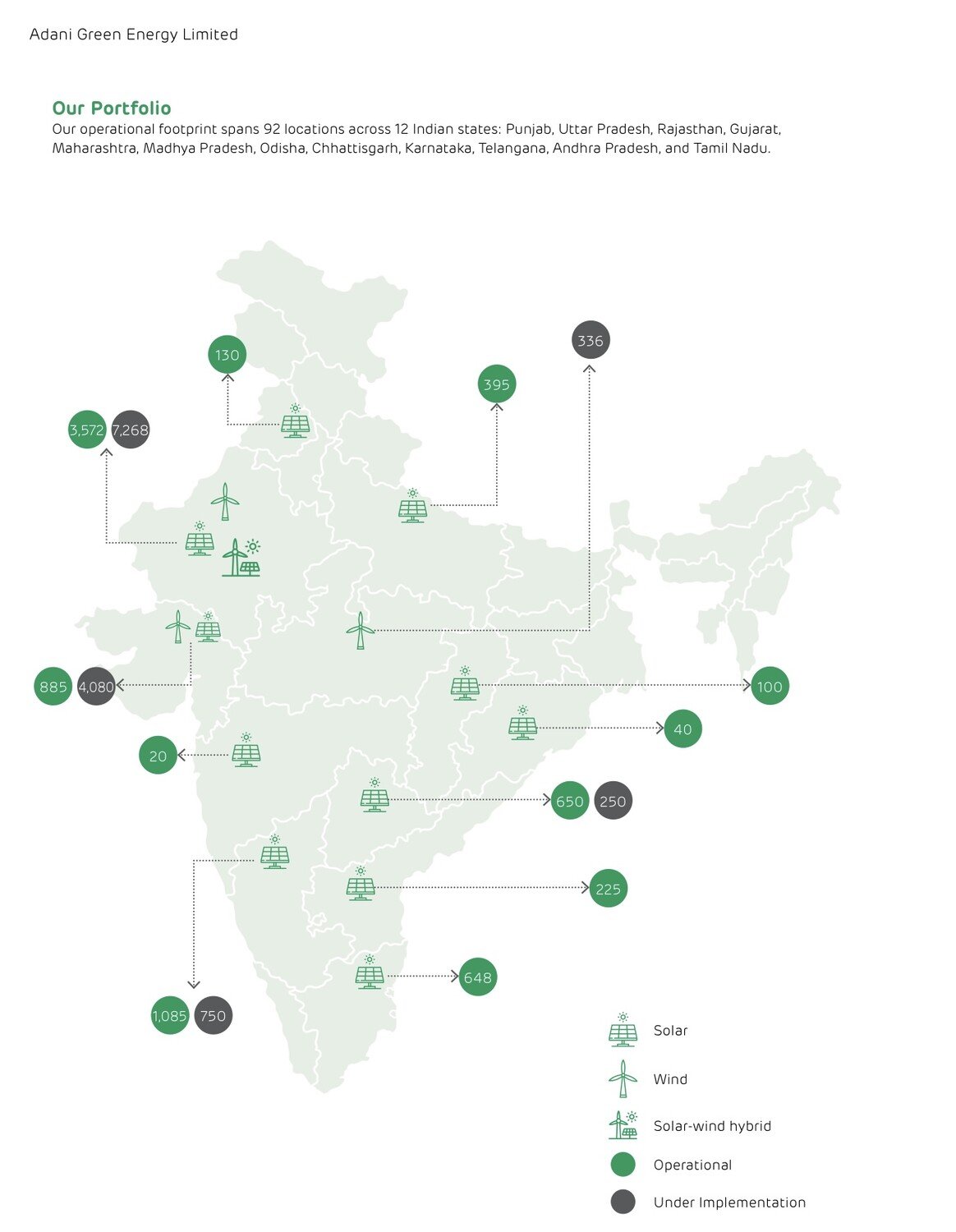

In 2020, Gautam Adani's conglomerate, Adani Green Energy Ltd., secured a landmark 8-gigawatt solar power contract, hailed as a major achievement in India’s renewable energy drive. The deal, which required the company to build substantial new manufacturing capacity for solar cells and panels, was initially celebrated as a key element of India's global commitment to addressing climate change. However, the contract’s scale and the controversy surrounding it have since become central to a crisis that challenges not only Adani’s diversified empire but also the credibility of India’s renewable energy sector.

At the heart of the issue are accusations from U.S. prosecutors that Adani and his associates paid or promised over $250 million in bribes in exchange for securing this lucrative deal. The case highlights significant concerns about the transparency and integrity of India's renewable energy auction system, which has generally been praised for its role in driving down prices and increasing the pace of renewable energy installations in the country.

The Record Auction and Its Flaws

The 2020 solar auction was exceptional in both its size and scope, representing a fourfold increase over typical government tenders. This massive scale, while designed to push India toward energy independence, exposed flaws in the auction system and underscored the government’s heavy reliance on a few large players, like Adani, to realize its vision of self-reliance. India, despite its heavy dependence on coal, has become the third-largest solar market globally, but its transition to green energy has faced challenges, particularly with large-scale projects.

The auction’s terms, which combined electricity generation with manufacturing commitments, were designed to attract investment into domestic solar manufacturing. However, these terms struggled to attract sufficient competition. The Indian government had to sweeten the offer in 2019 by increasing capacity, raising price limits, and allowing more time for project completion. This created an environment where Adani, with few competitors, could secure the deal.

Adani won the contract to sell solar power at 2.92 rupees (approximately $0.03) per kilowatt-hour, which was significantly above the average price from smaller auctions that year. In addition to its generation obligations, Adani committed to building factories capable of producing 2 gigawatts of solar cells and modules annually, despite India’s total production capacity being just 3.5 gigawatts at the time.

Allegations of Corruption

However, the deal faced significant hurdles in execution. India’s system of securing generation commitments before finalizing power purchase agreements left the Solar Energy Corporation of India (SECI) struggling to find buyers for the electricity generated at the low rates promised in the auction. According to U.S. prosecutors, this gap in securing buyers led to the alleged bribery scheme, with Adani executives reportedly meeting local officials to facilitate agreements with power distributors. It is claimed that the bribes amounted to $265 million.

To mitigate these issues, Adani reportedly lowered the initial price of its electricity by about 15%, which helped secure power purchase agreements with regional utilities in 2021. Additionally, disclosures from Adani Green suggested that favorable terms were negotiated, including the right to sell 16% of the contract’s power on the spot market and the ability to import solar modules, despite India’s push for domestic production. These terms were seen as advantageous for the company, adding significant financial value to the project.

Broader Concerns About India’s Auction System

While the case centers on the 2020 solar auction, it has raised broader questions about the structure of India's renewable energy auctions and the potential for market manipulation. Critics point out that large players like Adani, which can combine different technologies like solar and wind generation, have an edge in auctions that do not sufficiently level the playing field for smaller competitors.

For instance, a 2024 tender floated by Maharashtra’s state power distribution company included a mix of coal and solar generation, but the specific structure of the contract favored Adani’s ability to supply both technologies, resulting in a higher cost to consumers compared to potential alternative configurations like wind-solar-storage combinations. This could ultimately lead to higher electricity prices for consumers, as fluctuations in coal prices would likely be passed on.

Experts argue that the success of India’s renewable energy auctions in driving down clean power costs has been tempered by conditions that limit competition. Auctions that lack technology neutrality, for example, may result in higher costs for consumers and reduce the competitive pressures that drive innovation and cost reduction in the sector.

Adani’s Political and Legal Challenges

Gautam Adani, who has long been a close ally of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, has faced increasing scrutiny as these allegations have come to light. Despite consistently asserting that he does not seek special treatment, the investigation into Adani’s empire by U.S. authorities has raised doubts about whether his company has benefitted from favorable treatment in previous renewable energy tenders as well. For instance, critics note that in some auctions, terms have seemed tailored to Adani’s strengths, reducing competition and potentially driving up prices for consumers.

The legal troubles, particularly following allegations of corruption, are compounded by the shadow cast over India’s renewable energy sector. Foreign investors, including Adani’s partner TotalEnergies, have expressed caution about making further investments until the legal outcomes are clearer. TotalEnergies has stated that it will not invest further until the results of the U.S. investigation are resolved, highlighting the potential impact on India's clean-energy transition, which relies heavily on foreign capital.

Potential for Reform

This situation raises important questions about India’s auction system and the governance of its energy markets. Analysts suggest that tightening the auction process to ensure greater competition and transparency may be essential for maintaining confidence in the country’s renewable energy sector. Currently, government entities like SECI and NTPC Ltd. are responsible for conducting auctions, but they often face delays in securing buyers for the electricity, a situation that places financial strain on developers. Reforming this process could help mitigate risks associated with large-scale projects and ensure a more competitive and sustainable renewable energy market in India.

As the investigation into the bribery allegations continues, the future of India’s renewable energy sector may depend on how it navigates these challenges. The outcome of the case will likely shape the country’s risk perception in the global energy market and influence the pace of its green energy transition.